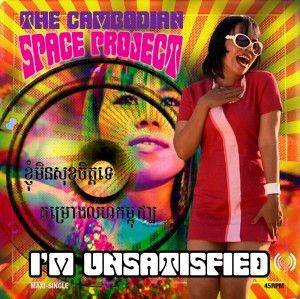

I recently visited Hobart for my cousin Julien’s wedding, a spectacle that I’ve been privately referring to as the ‘unicorn sighting’, Julien being an exotic creature and someone not inclined towards matrimony or the domestic sphere (I’ve mentioned him earlier in this blog in connection with his band: The Cambodian Space Project). Julien and Channthy married in a private ceremony in my Mum’s back garden, underneath an arch I’d decorated with ferns, red roses and white agapanthus. While decorating the arch, I grooved on the idea of residual paganism in Christian ceremonies, wondered about the possibility of hiding small animal icons in the arch, or burying them in the garden nearby. Then I decided that if my family caught me doing it they would probably think I was a nut. In the end I chose a particularly fecund piece of fern frond, the pale green bit right at the end which ends in a delicate curlice, and hid it at the top of the arch behind the roses. John Olsen draws these kind of curlices, I’ve always loved them, they’re all over the ancient pottery of the Agean Sea, and sometimes found in indigenous art forms; a dodgy art lecturer once suggested to me that they represent the infinite. For me they’re both a nice shape and something that symbolises new beginnings. A spiral is my eternal Spring, no puns intended.

Another highlight of the latest Hobart trip was a visit to the newly opened MONA, Museum of Old and New Art. Mum dropped me off, I left her with Sophie as my darling toddler was heading towards Erich Wurm’s immaculate ‘Fat Car’ sculpture with outstretched arms and sticky fingers. In Sophie’s defence, I think she confused it with the bright red car that the Wiggles get around in. I like Wurm’s stuff, this was the first time I’d seen it in the flesh, kind of an exciting event for me. His fat sculptures brilliantly captures the essence of the times: the futility, mawish beauty, greed, relentless consumerism, self destructive neurosis and anxiety. They’re the visual equivalent of a hit record.

One of Erich Wurm's fat cars

I wish I’d recorded my feelings and impressions as I walked around the MONA space. I’d just spent a couple of hours in the gym so I was physically tired, and because I’d drunk a lot of water, I also badly needed a pee. If you’ve read anything about MONA, or visited the place, you’d know that one of its quirks is that the toilets aren’t marked. At all. If you need a toilet, to the point of worrying about wetting your pants, this strikes one as a particularly cruel piece of interior design. It made me think of two things: a school of architecture that used to incorporate false entrances and dead ends (apparently in one particular building, bike couriers used to dash in and run splat into a wall). And gender classification, how slippery it is, this idea that gender exists as a spectrum rather than an absolute state. Still, these ideas don’t help you when you badly need to piss.

I asked one of the security guards, a black guy with a London accent, and he pointed me in the right direction. MONA is underground, with dark walls and limited lighting. The combination of the guy’s lovely accent and the darkness caused an intense series of flashback memories of nights spent clubbing in London. This strange feeling of being drug-fucked in a nightclub, while looking at contemporary art, two different areas of my life fusing into one slightly mind-blowing experience.

MONA inspires claustrophia, anxiety, humour, frustration, thought, daydreams, new realisations, desire. It demands active participation from the viewer: this is its strength. It also manages to be quite annoying. Why? Things like the toilet signage (private musing that museum staff will get really sick of the constant query ‘where is the loo?’). Eschewing traditional signage and labelling the ‘O’, an electronic museum guide, provides artist biography, formal notes and a gonzo section with down to earth dialogue. Nice idea. The Gonzo section contained some gems, here’s some rough paraphrases: ‘Artist X lives in a shitty part of Manhattan’ ‘This artwork came with two invoices, not one, therefore we consider it two separate works’ ‘Artist Y is extremely good looking’ and ‘I paid half a million dollars for this piece of crap, so I’ve got to like it’.

The O content was mostly good, occasionally frustrating. I’m pretty straight: I like to deal with ideas with the personalities removed, like a piece of filleted fish. I understand there’s a person behind any idea, with their own biases and history, but I’m happy to accept this as the hidden structure that supports any piece of writing, kind of like a building’s foundations. With the MONA texts, I thought there was too much emphasis on the personalities of the people who put together the collection. Clicking the button on the O gadget is the equivalent of asking a question, and sometimes the text didn’t engage but deflected with humour and trivia. Clicking the same button multiple times usually got about three different responses. (It reminded me of Skinner’s early experiments on pigeons- the one where he got the birds to peck a button for food, and then experimented with which birds gave up first when the button stopped working). When you honestly want to know more about something, this can be infuriating. Like I said, I’m pretty straight.

The art was great. It’s one of the few spaces I’ve ever seen, actually the only one, where you can segue from a pen and ink drawing by Kathyrn Del Barton, with a river pouring out of her vagina, to an upright Egyptian mummy, black rimmed eyes gazing stoically at the museum patrons. Here are some flashes of stuff that made an impression: a white cube built into the museum, with pale Perspex door; inside a bank of video screens with people singing Madonna songs. A series of delicate ink and watercolour drawings, people, animal and tree forms, the O blurb sagely noting ‘there’s nothing we can say about these drawings- you just have to look at them’. An underwater wunderkammer containing carved antiquities, some of them copied from the originals, no weeds or bubbling bridge but fish swimming austerely in and out of the ancient forms. Flesh, naked flesh, with slogans written on it with felt tipped pen. A huge metal sculpture of a head, small holes providing windows through the skull into a poetic representation of a mind in action. A Juan Davila oil painting, a kangaroo felchering either Burke or Wills, I’m not sure which. Eric Wurm’s shiny red obese car. The huge Sidney Nolan rainbow snake, a surprisingly conventional backbone to the collection, a structure from which the other forms all seem to emanate. An ancient coffin, so small that a modern human would need to curl themselves into a ball to fit into it. A white library, every book blank, careful white tables with more blank paper. And again questioning the capacity of humans to aborb information in an increasingly complex world, a waterfall of words, the most popular search terms in Google, frequently updated, each liquid word hanging for less than a second before splashing onto the ground below, an eternal torrent of information.

A rich vein of anxiety running through everything, an overload of sex and death, the resonance of an individuals act of choice, a personal collection made public. It made me feel many things: creeped out, impressed, amused, moved, thoughtful, annoyed, alive, overwhelmed, surprised, aroused, but never disappointed or indifferent. I’ve got to say, opening a world class museum in Hobart, a small regional city with a perennially fragile economy, is an act of supreme generosity: locals are already talking about the Bilbao effect.

There were two artworks in the collection that loosely relate to my personal history: Chris Ofili’s black elephant dung Madonna, and Damien Hirst’s spin painting. Chris was the year ahead of me in the Painting Department of the Royal College of Art; after college I watched him become famous. I remember that he was a nice guy who worked hard in the studio, chased fame with a singular tenacity outside it, but once he achieved it seemed less than ecstatic. A memory: sitting in the rooftop college bar, drinking beer with RC, who see’s one of Chris’ ‘ELEPHANT SHIT’ stickers on the tabletop, and sets to peeling it off with a stubby thumb and forefinger, muttering as he does it ‘self promotional bullshit’. I said ‘I thought you liked him?’ ‘I do’ muttered RC, doggedly continuing to peel.

A final flash of memory: walking down an alleyway in Mayfair, on my way to an exhibition opening, and seeing Chris and his beautiful girlfriend climbing out of a car up ahead. She was extremely tall, with very pale skin and green eyes, wearing a black leather jacket. It was like watching a still from a movie.

After I graduated from the Royal College, I got a studio in Brixton, South London. I can’t remember how I found the studio; I do remember going around with a couple of artists and an architect, inspecting derelict warehouses, empty for years, discussing whether we could turn them into artists’ studios. One of them had a rotting wooden floor and a huge pyramid of pigeon droppings; we walked quietly and gently, scared of falling through to the floor below, I remember kicking open a rusted shut door. The architect owned quite a few old buildings. Eventually two of us ended up with studios on a site he owned in Brixton, three old warehouses and a decaying Georgian mansion. Damien Hirst had a studio there but by this time he was quite famous and his assistants seemed to make most of the work. The Brixton studio team used to make the formaldehyde animals and the spin paintings. Always the horse-trader, RC asked me if I wanted a job pumping formaldehyde ‘I can probably get you in…’ I was still at the idealistic/stupid end of the professional spectrum and replied no, that I didn’t want to spend my life making another artist’s work for them. RC looked impressed, and I continued washing dishes for a living; yep, I was dumb. Probably still am.

I had a private chortle when I saw the spin painting in the MONA collection and read the O blurb. I remember this shitty post industrial studio complex in the middle of a South London housing estate; freezing cold, grey skies and constant rain; a large collection of rusting cars guarded by a savage dog; huge iron gates that were supposed to keep out intruders (they didn’t); giant rats with orange ticks; mud. It was so cold that one artist used to paint in an army surplus parachute jumpsuit and another built himself a plastic room within his studio to keep warm. In the middle of the central courtyard there was an overflowing rubbish skip. From time to time the skip housed rejects from some really good artists: I remember pulling out an early Nicky Hoberman, once a failed spin painting got chucked out (there was a fuss when someone later tried to sell it) often there were tins with the remains of the enamel paint used to make the spin paintings. One of the artists painted their kitchen cupboards with the remnants. Hirst’s assistants used to joke about making the spin paintings, hold up three paint tins of warm orange colours with a mocking declamation of ‘Autumn!’, brandish tins of pale green with a cry of ‘Spring!’ Artists in the other studios were quietly bemused by the success of the spin paintings.

The head of Hirst’s studio team was fairly obnoxious; when his wife had a kid he sweetened up a bit, but prior to that he was usually unfriendly. One day I knocked on Hirst’s studio door (I was living in my studio in the Georgian mansion at this stage) to give them an invitation to an American friend’s exhibition. He was rudely dismissive, enjoying the power to be rude to someone when they want something, and I felt pissed off and hurt. I don’t think I would have minded so much if I’d been plugging my own show, but because it was someone I liked, who was going through a rough time, I resented it enormously.

A few nights later I went to the pub with a friend, drank bucket loads of beer, and came home to the studio urgently needing a piss. (I should add at this point that the studios were sometimes without running water and electricity). I’d read a review of a contemporary Shakespeare production, one in which Lady Macbeth urinated on the stage floor during each London performance. In an interview with the actress, someone asked her what she thought about peeing on stage in front of a crowded house. She replied with gusto: ‘I usually think: that was a damned good piss’. And I’ve always been a fan of the dubious story about Jackson Pollock urinating in Peggy Guggenheim’s fireplace. So on this particular night, with a bladder as bloated as an airship and with the memory of the rude assistant fresh in my mind, I staggered over and peed on Damien Hirst’s studio doorstep. It was incredibly satisfying and, just like the actress, I thought to myself ‘damn, that was a good piss’. Anyway, when I was wandering around MONA looking for the toilets, it’s something that I remembered.