Yesterday my Grandmother died: she was 93. Up until a few months ago, she was still living at home, and fiercely independent. Even the day before she died, she was still getting up, dressing herself and talking to people. She was the kind of person who believed in doing things well, and fighting any battles that needed to be fought with characteristic verve, determination and style.

As a young Catholic mother in New Zealand, my Grandmother raised six children, before moving to the island of Tasmania with her husband. My Grandfather built a house for his family in the industrial town of Burnie, and continued to chase his public service career, eventually becoming head of his department. A passionate rugby player, my Grandmother used to joke that if he’d known Tasmania didn’t have a rugby union team, he would never have moved there. After a cruel illness, he died early; my Grandmother’s bravery during this time was phenomenal.

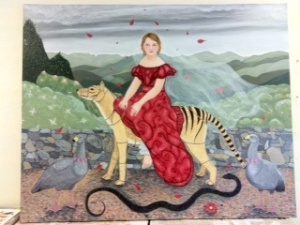

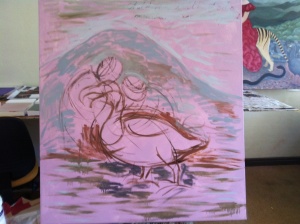

My Grandmother was a strong supporter of the Arts, in all their forms. She painted and wrote poetry, and was always amazingly perceptive in her critiques of both creative works and people. In her early life, she taught art at Fahan School, a private girls college. She later managed the rare feat of turning her passion for creativity into a commercially viable concern.

With her sons Charlie and Mark, and husband Bernard, my Grandmother started Hobart’s first commercial gallery. (Or at least I’m fairly certain it was the first, but I’m happy to be corrected on this point). Salamanca Place Art Gallery was initially located in an old sandstone warehouse, on the corner of Salamanca Place and Wooby’s Lane, in a sprawling strip of buildings that once serviced Hobart’s notorious docks. The Gallery survived a couple of recessions, and at various times showed works by artists such as Tim Olsen and Brett Whiteley. Charlie eventually sold it to Dick Bett, who first moved his premises up the road, and re-named the business Dick Bett Gallery, and later to a shop front in North Hobart, where it traded as Bett Gallery. When Dick passed away, his children inherited the business, and it continues to trade as a respected contemporary art space.

I find it difficult to express the profound impact she had on both myself and her other grandchildren (Julien, Duncan, Rachel, Corinne, Natalie and Bernard). I remember having a conversation with my Grandmother, I must have been about twelve, when we discussed London’s famous art schools. She told me about the Royal Academy’s raised tiers in their life drawing room, and also about the Royal College. I vaguely recall asking her the difference between the two institutions, and she said something about the interesting painters, such as David Hockney, who had trained at the RCA. At that moment, I decided that I’d study at the RCA, which is something I eventually did.

In many families, working as an artist is actively discouraged. A Chinese friend once told me that she became an accountant because her parents told her that being an artist was “the way of the pauper”. I suspect that the same message is delivered across cultural boundaries everywhere. I rarely doubted that creativity was a vocation, and a worthwhile pursuit, and something that ranked high above most other professions, in that it spoke to the human spirit. In my family, my mother is a former State Gallery curator, and now paints and pots; my aunty established a feminist bookshop in the 1970s, taught English for many years, and now makes handmade books; my cousin Julien is a professional musician and talented writer; while my cousin Corinne sews like a dream and runs a creative business. Various other family members paint, garden, cook, curate, write, play, paint and build. I mention this because it is unusual for so many people in a family to act creatively, and this is largely due to my Grandmother’s influence.

When I was a young woman, living in London, my Grandmother acted as my psychic anchor. Life in a large city can be a lonely, expensive and disconnecting experience. During this time, I often wrote her letters, and when she was dying, discovered that she had saved them all. My mother gave me a large manila envelope with ‘Helen’ written on the front, and inside were these records of my former self. For some reason, I found the fact that she had kept them incredibly moving.

Grief is a strange emotion. For years now, whenever I visited Tasmania, at the end of each holiday I would say goodbye to my Grandmother. Each time I would think to myself ‘this is the last time I will see her’, and I took a mental snapshot of her face. In my memory is a perfect record of these final moments, lined up like photographs in an album. I kept on applying for artist residencies in Tasmania, hoping to spend some of her final years in the State, but for some reason, though my career functioned well elsewhere, I could never find much opportunity in my own State. I admit to a lingering grudge.

The last time I said goodbye, it really was the last time. The doctors gave her a blood tranfusion, which kept her alive for about a month, and allowed her family and friends to share some precious time before she passed. On our last day in Tasmania, Sophie and I spent the morning in her hospital room. We were there with my cousin Rachel, aunty Pam and my mother. I wheeled Sophie, an energetic five year old, around on my Grandmother’s mobility device and we talked and laughed. When we left, I turned around in the corridor, and blew my Grandmother a kiss. She blew one back, and I have another photograph in my mind of this moment. It’s something I will always treasure.

R.I.P. Marjorie Leonora Hill (nee Gregory)